Astronomers imaging the cosmos with the Webb Space Telescope have found the most distant active supermassive black hole yet. The black hole was “seen” as it was around 570 million years after the Big Bang.

The universe is about 13.77 billion years old, meaning the newly discovered black hole popped up when the universe was just over 4% its current age. The black hole lurks within the galaxy CEERS 1019, and at nine million solar masses, is the least massive of any supermassive black hole yet seen in the early universe.

For comparison, the black hole at the center of the Milky Way—Sagittarius A*—is less than five million solar masses. Supermassive black holes are some of the densest objects in the universe and can be billions of times the mass of our Sun. Like all black holes, they have such intense gravitational fields that not even light can escape their event horizons, leaving astronomers to image the “shadow” in which the black hole resides.

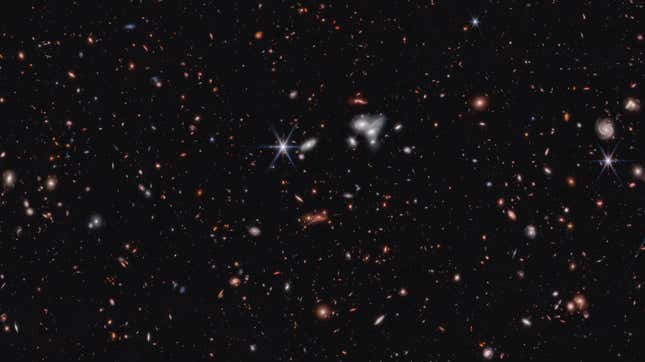

CEERS 1019’s black hole was spotted by a research team conducting the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science Survey, or CEERS. The survey takes deep field images of the cosmos, which cover sweeping swaths of the sky and peer deeply into them, allowing scientists to see some of the universe’s most ancient light.

The newest CEERS mosaic image is 510 megabytes—beyond what this website can handle—so if you’d like to peruse the cosmos in all its digitized glory you can download the full-size image here. The combined image contains about 100,000 galaxies.

Besides CEERS 1019, the survey team spotted eleven galaxies that date to when the universe was between 470 million years old and 675 million years old, and two other black holes dating to around one billion years after the Big Bang, according to a Space Telescope Science Institute release.

Four papers on CEERS Survey data are set to publish in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The papers announce the discovery of the ancient black hole, detail the spectroscopy of active galactic nuclei at high redshifts, the confirmation of distant galaxies, and an initial characterization of their properties.

“Looking at this distant object [CEERS 1019] with this telescope is a lot like looking at data from black holes that exist in galaxies near our own,” said Rebecca Larson, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin and lead author of one of the CEERS papers, in the STScI release. According to the release, Webb is detecting more galaxies at these extreme distances than researchers expected it would.

Black hole evolution is still something of a black box in astrophysics, so being able to see such ancient black holes is a boon to researchers trying to understand how the universe’s most massive objects grow and affect masses around them.

The CEERS Survey is providing data that will help scientists decipher black holes, just as gravitational wave observatory data is clueing astrophysicists into the gravitational wave background generated by supermassive black holes.

But supermassive black holes have to grow out of something, and a dearth of intermediate-mass black holes in the cosmos has only raised more questions about how stellar-mass black holes give rise to such cosmic behemoths.

“Researchers have long known that there must be lower mass black holes in the early universe. Webb is the first observatory that can capture them so clearly,” said Dale Kocevski, an astronomer at Colby College and lead author of another CEERS paper, in the same release. “Now we think that lower mass black holes might be all over the place, waiting to be discovered.”

Next week will mark a year of Webb Space Telescope science observations; in other words, the trove of insights are just the beginning for the powerful observatory.

IIRC, it wasn't too long ago that we didn't have any images of black holes... their existence was only theoretical.